The Neuroeconomic Cycle Driving Empathy, Fear, and the Shape of History

Updated August 2025 — Now includes the full neurochemical model of Turning transitions, revealing the hidden triggers that drive history’s most dramatic shifts.

What if history doesn’t just repeat? What if it pulses, rising and falling in ways we rarely notice until it’s too late?

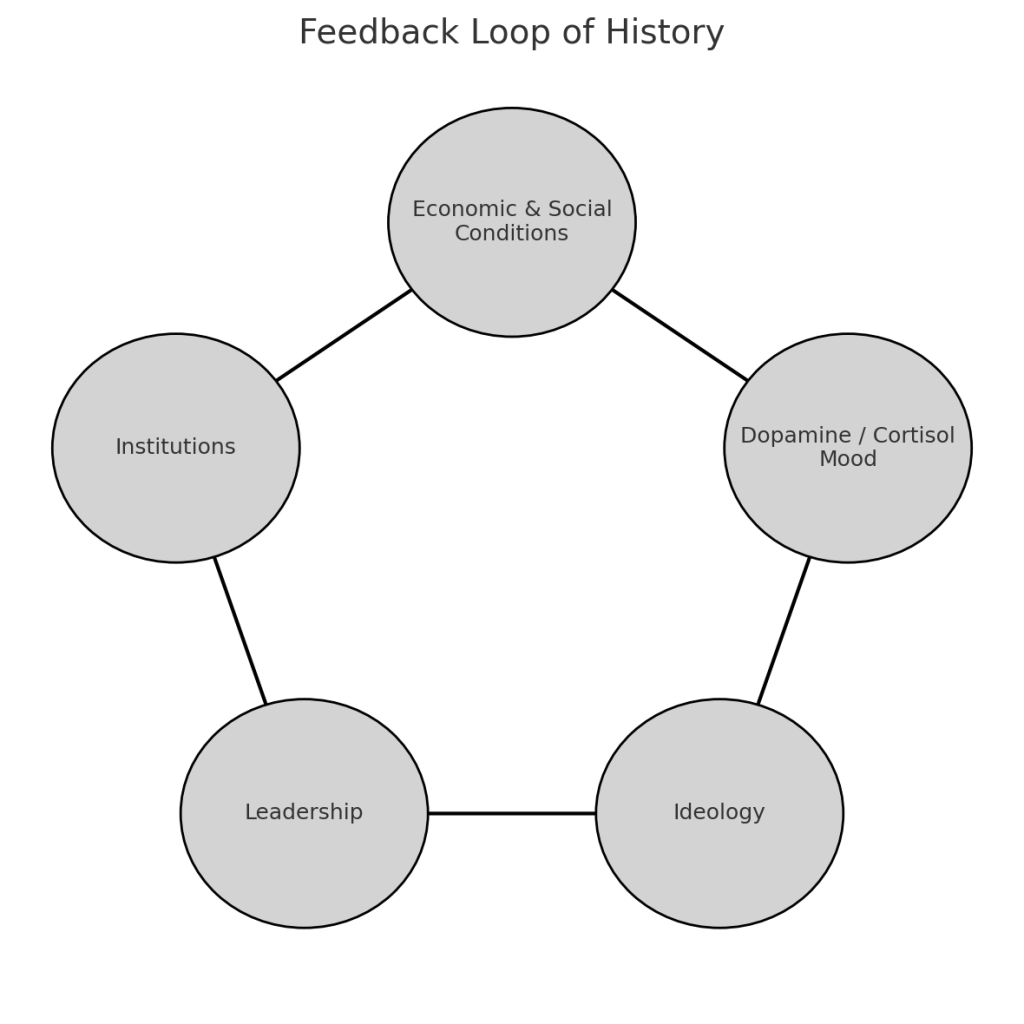

This article started as a simple list of events that shaped the world we live in. But as I followed the threads, I found something deeper: a hidden feedback loop connecting economic stress, brain chemistry, ideological shifts, and the generational cycles described by Strauss and Howe’s “Four Turnings.”

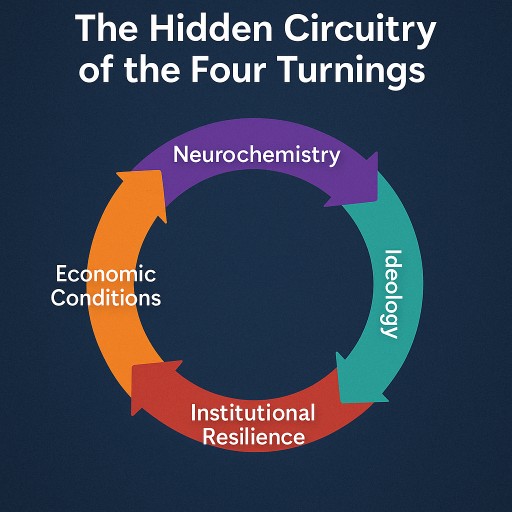

The Hidden Circuitry of the Four Turnings explores that loop, how it might explain the rhythm of fear and hope that shapes our society, and whether we might soften the impact of the next wave before it crashes.

Who This Is For

This essay is for curious readers: those who sense deep patterns beneath the chaos of modern life and want a clearer picture of how history, psychology, and society interlock. You don’t need a background in neuroscience or generational theory. Just bring your intellect, your instincts, and a willingness to follow the deeper currents beneath our political storms.

The Hidden Circuitry of the Four Turnings

What if history doesn’t just repeat—it pulses?

For decades, the Strauss–Howe generational theory has described an 80-year cycle of American history, divided into four “Turnings.” … But while the Turnings map the shape of history, they don’t explain why the cycle occurs. What drives it? What gives it force, urgency, emotion?

What if the answer lies inside us, not just in the abstract “spirit of the age,” but in the way our civilization’s nervous system responds to stress and stability? Like a living organism, a society processes stimuli, generates chemical signals, and shifts behavior in predictable ways when it feels safe, threatened, or disoriented. If we could read these signals, we could see the why behind the Four Turnings — the neurochemical engine that moves them.

Emerging research in neuroscience and psychology suggests that mass behavior—ideological rigidity, empathy, rebellion, conformity—may be influenced by more than just events. Our economic conditions influence our biology, especially brain chemistry like dopamine (a reward-seeking neurotransmitter that fuels curiosity and optimism) and cortisol (a stress hormone that heightens vigilance and control), which together govern motivation, fear, openness, and trust.

When the economy crashes, dopamine drops. When hope rises, so does flexibility. Fear tightens. Safety relaxes. And these chemical shifts ripple outward into politics, crime, culture, and collective identity.

This article explores a new idea: that the Four Turnings may be underpinned by a multi-level feedback loop connecting economics, brain chemistry, ideology, leadership, and institutions. A system that moves not just across time, but through us.

If this circuitry exists, can we see the warning signs as we approach another breaking point? And if we can’t stop the cycle entirely, could we at least soften its hardest turns?

A Brief Tour of the Four Turnings

History doesn’t move in straight lines; it moves in seasons.

According to Strauss and Howe, American history cycles through a repeating pattern roughly every 80 to 100 years, called a saeculum. Each saeculum is divided into four Turnings, each lasting about 20–25 years, reflecting a generational mood swing that reshapes society. You can think of a saeculum as roughly equivalent to a human lifetime — moving through youth, rebellion, decline, and renewal — but played out on a societal scale.

The Four Turnings unfold in this order:

1. The High – A time of collective confidence and institutional strength, following a major crisis. Post–WWII America (1946–1964) is the textbook High: optimism is high, trust in institutions is strong, and shared purpose run deep.

2. The Awakening – As prosperity grows stale, the next generation pushes back. This is a time of spiritual upheaval, idealism, and questioning of established norms. Think of the 1960s and 1970s: civil rights, anti-war protests, feminism, environmentalism, the counterculture.

3. The Unraveling – Institutions weaken. Cynicism rises, trust erodes, and the social fabric frays. Individualism peaks while the social fabric frays. The 1980s–2000s saw deregulation, wealth inequality, and the rise of culture wars.

4. The Crisis – The unraveling reaches a breaking point. Institutions fail. Conflict surges, urgency dominates. The 2008 financial crash, climate emergencies, and political extremism may mark our current era.

It’s worth noting that not every Turning arrives on a precise schedule. Historical crises and realignments sometimes come earlier or later than expected, and Strauss and Howe’s timeline predictions have faced fair criticism. The framework here addresses some of those critiques by explaining the why behind the pattern, the feedback circuitry that drives it, which is less about fixed dates and more about recurring human dynamics shaped by economic, emotional, and institutional forces.

Where we go next depends on how this Crisis resolves.

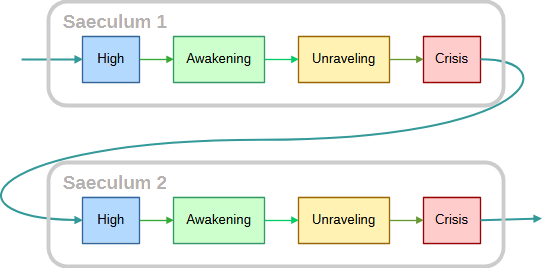

Each saeculum cycles through four Turnings: High, Awakening, Unraveling, and Crisis.

This diagram shows the flow of transitions within a saeculum and the saeculum-reset transition from Crisis back to the next High.

The historical saecula listed below can be read using this same pattern.

| Saeculum | High | Awakening | Unraveling | Crisis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revolutionary | Colonial Order (1701–1746) | First Great Awakening (1746–1773) | Imperial Strain (1773–1794) | American Revolution (1794–1820) |

| Civil War | Jacksonian Era (1820–1844) | Transcendental Awakening (1844–1860) | Sectional Conflict (1860–1865) | Civil War & Reconstruction (1865–1884) |

| Great Power | Gilded Age Stability (1884–1908) | Progressive Upheaval (1908–1929) | Roaring Twenties (1929–1939) | Great Depression & WWII (1939–1946) |

| Millennial | Postwar Consensus (1946–1964) | Counterculture Rebellion (1964–1984) | Culture Wars/ Neoliberalism (1984–2008) | Financial Collapse to Present (2008–?) |

Table 1: American saecula and their Four Turnings

The Chemistry of Fear and Hope

Dopamine is often called the “reward chemical,” but it’s more accurate to say it governs motivation: how much we care, how much we want something, and how open we are to risk and new experiences.

When dopamine is high, people feel optimistic, flexible, and energized. They explore. They trust more easily. They can imagine a better future and work toward it. When dopamine is low, the opposite occurs: fear rises. People become rigid, suspicious, protective. They cling to certainty and close ranks. Creativity and empathy decline.

This isn’t just personal chemistry. When large numbers of people experience stress or uncertainty at the same time, their collective dopamine tone can shift. The results appear in rising crime, addiction, conspiracy theories, and authoritarian movements, but also in eroding trust, political polarization, and social fragmentation.

You can think of dopamine as the thermostat of a society’s mind. Just as thermodynamics governs how heat and energy flow through physical systems, dopamine regulates the flow of mental and emotional energy: motivation, curiosity, and trust. When conditions feel stable and hopeful, dopamine rises, fueling exploration, flexibility, and imagination. But when stress and chaos dominate, dopamine drops, and with it comes fear, rigidity, and withdrawal. Like a heat engine shifting modes, society’s cognitive climate changes, seeking predictability over openness.

This shift isn’t only emotional, it’s informational. People aren’t just reacting to threats; they’re trying to reduce uncertainty and restore a sense of order, even if it means becoming more closed-off or authoritarian.

But dopamine is only half the equation. As uncertainty becomes chronic, cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, rises. While dopamine promotes openness and exploration, cortisol reinforces vigilance, control-seeking, and fear. When it stays elevated, it impairs memory, narrows focus, and reduces emotional regulation. Societies saturated in cortisol feel overwhelmed, not just politically but cognitively. The brain rewires for survival, not imagination. The result isn’t just stress; it’s structural.

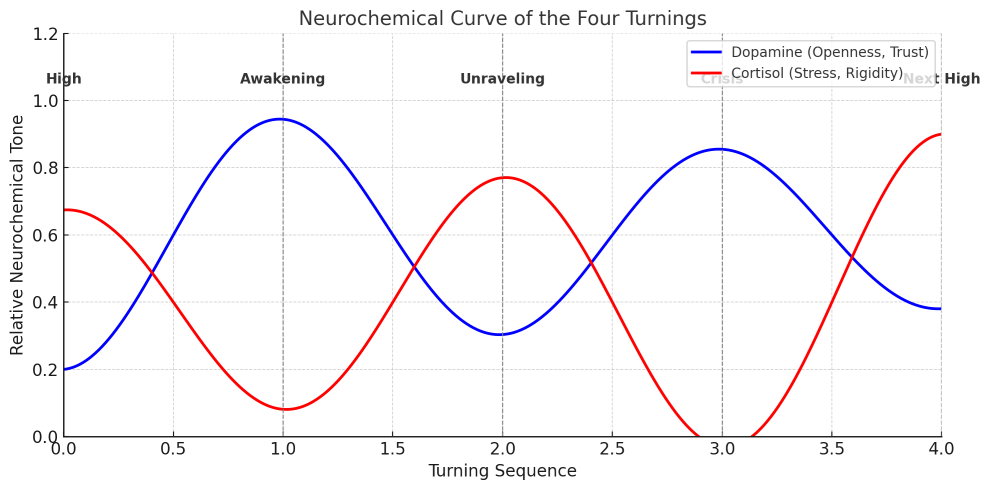

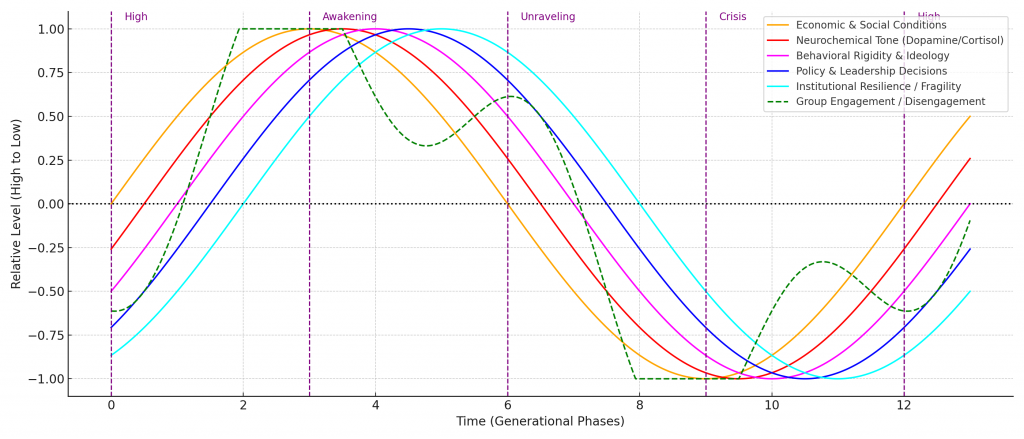

The Four Turnings can now be seen as phases in a civilization’s neurochemical cycle: a rise and fall of dopamine and cortisol that changes how we think, feel, and act together. This cycle explains not just the mood of each Turning, but how we move from one to the next.

The Neurochemical Cycle of a Saeculum

- Crisis → High Turning (Cortisol Peak) — Triggered by a Seismic Narrative Shift (a sudden event or cluster that flips society’s mood almost overnight) or, more rarely, a Shedding Transition (a gradual erosion of old norms and narratives without a single defining rupture). Characterized by stress, urgency, polarization, and collapse of legacy systems. Cortisol dominates, driving survival-mode thinking, hierarchy, and conformity. Ends when decisive action or resolution allows cortisol to fall.

Example: August 14, 1945 — Times Square erupts. Strangers kiss in the street, factory whistles scream, and war-weary America exhales for the first time in years. The stress chemistry of the Depression and World War II starts to drain, replaced by the cautious euphoria of rebuilding.

- High → Awakening Turning (Regulation Zone) — Cortisol drops, dopamine stabilizes. Society builds new norms, trust, and infrastructure. Institutions gain legitimacy; social cohesion is high. Emotional climate is balanced and future-oriented. Dopamine begins a slow rise.

Example: 1962 — John Glenn orbits the Earth. Families huddle around black-and-white TVs, marveling as the impossible becomes real. The stable optimism of the High fuels a hunger for exploration, and dopamine begins its long, slow climb toward idealism and rebellion. - Awakening → Unraveling Turning (Dopamine Peak) — Stability enables idealism, identity quests, and rebellion against inherited norms. Dopamine surges, fueling creativity, individualism, and social criticism. Institutional trust begins to erode, not from crisis, but from a growing desire for purpose beyond stability, a dopamine-driven search for meaning that fuels cultural critique and challenges to the established order.

Example: August 1969 — Woodstock. Half a million people camp in a muddy New York field, swapping food and slogans about peace and love. Institutions look stodgy and irrelevant against the raw, high-voltage energy of counterculture. - Unraveling → Crisis Turning (Dopamine Withdrawal) — Cultural fragmentation, cynicism, and political gridlock set in. Trust collapses, narratives splinter, and dopamine drops sharply. Cortisol begins to build in anticipation of a new Crisis.

Example: March 2020 — COVID lockdown begins. City streets empty overnight. Supermarket shelves go bare. The mood flips hard into survival mode, setting the stage for the next Crisis arc.

Cycle Reset — The saeculum closes when a society-wide mood rupture occurs, triggered either by a Seismic Narrative Shift (a high-magnitude event or cascade that flips public mood quickly) or an accumulated Shedding Transition (a slower erosion of norms without a single defining flashpoint). Either path resets the cycle, carrying forward both strengths and unresolved fragilities into the next Crisis.

Transition Timing Matters

- Shock transitions happen when society is emotionally primed and a triggering event arrives with enough symbolic weight to break the old mood instantly.

- Shedding transitions happen later; society drifts out of one mood into another without a single defining rupture, often rejecting multiple “almost big enough” events before finally tipping.

- In both cases, the public’s emotional readiness, not just the size of the event, determines whether the Turning shifts.

This cycle isn’t deterministic. How it feels, and how destructive or constructive each Turning becomes, depends on a society’s maturity: its ability to regulate these swings like a skilled mind regulating its own moods. Dopamine and cortisol aren’t just brain chemicals; together, they’re a social weathervane, shaping not only the mood of a whole society, but also the baseline chemistry each generation will carry into adulthood.

Generational Chemistry

The Four Turnings aren’t just political or cultural phases; they are lived neurochemical climates. Each generation breathes in the mood chemistry of its formative years, and that “atmosphere” leaves a lasting imprint. A cohort coming of age under rising cortisol learns different reflexes, fears, and priorities than one maturing under rising dopamine.

For example, Artist generations often grow up during Crises, when stress is high and order is imposed. They experience strong external structure and tend to internalize a high degree of social sensitivity and conformity. Nomads often come of age during Awakenings, when institutions are questioned, disorder rises, and adults seem distracted. Their emotional environment is less stable, their protections more fragmented, and the result is a generation more skeptical, self-reliant, and pragmatic.

These early chemical fingerprints aren’t just psychological quirks; they reflect social neurobiology. Cortisol and dopamine shape openness, trust, impulsivity, and worldview. If you grow up surrounded by order, predictability, and optimism, your brain wires one way. If you grow up in chaos, distrust, or neglect, it wires another. Over time, these generational imprints feed back into the broader societal mood cycle, making the swings between Turnings anything but random.

The Civilization’s Nervous System and Maturity

A civilization can be thought of as a living organism with a nervous system: a distributed network that senses change, processes meaning, and coordinates action.

- Dopamine is its curiosity-and-exploration signal, opening it to novelty, risk, and innovation when conditions feel safe.

- Cortisol is its danger-and-vigilance signal, narrowing focus, prioritizing survival, and enforcing cohesion when threats loom.

Major events — whether wars, economic booms, pandemics, or cultural revolutions — are first felt as sensory inputs. They ripple through the social body via information networks, media narratives, and direct lived experience. These signals are then “interpreted” through cultural memory, institutional filters, and generational outlooks, triggering emotional and political reflexes.

Just as a biological nervous system can be dysregulated — overreacting to minor stimuli or failing to respond to serious threats — a civilization’s nervous system can also misfire. Chronic stress can keep cortisol artificially high, producing rigid, defensive politics. Prolonged comfort can inflate dopamine beyond adaptive bounds, fueling reckless risk-taking or cultural fragmentation. The health of the system depends not only on strength of response, but on how proportionate and well-matched those responses are to reality.

From Nervous System to Maturity

Because civilizations process information and respond to stress in patterned ways, we can think of them as operating at different maturity levels, much like individuals. In biological terms, a mature nervous system can regulate itself, recover from shocks, and integrate new experiences without losing its identity.

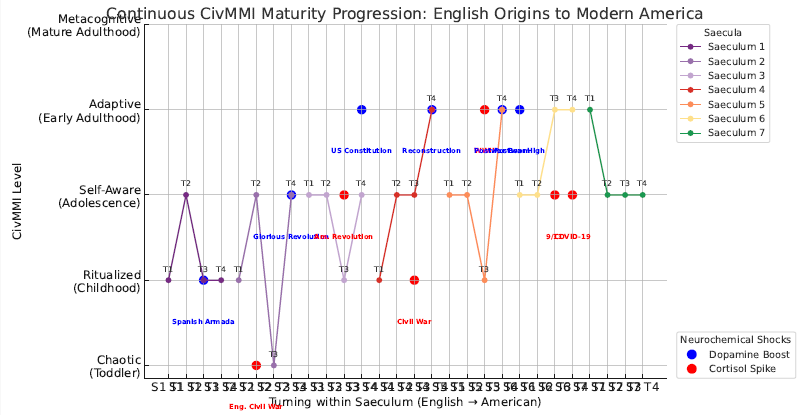

The Civilization Maturity Model Index (CivMMI) builds on this metaphor, rating how effectively a society regulates its emotional and institutional responses over the course of a saeculum. CivMMI has five broad levels:

- Chaotic – Poor regulation, constant overreaction or underreaction to events, fragmented narratives, fragile institutions.

- Ritualized – Stable forms exist but are rigid; responses rely on tradition and precedent even when conditions have changed.

- Self-Aware – Recognition of the cycle and willingness to adjust; some ability to coordinate across factions and mitigate extremes.

- Adaptive – Proactive in building buffers, maintaining trust, and steering transitions without waiting for full crises.

- Metacognitive – Reflective and self-correcting at the highest level; able to consciously alter feedback loops, shorten recovery times, and integrate long-term planning into cultural identity.

These levels also shape how a society moves between Turnings: a Level 4 “Adaptive” culture might absorb a Seismic Shift with minimal long-term damage, while a Level 1 “Chaotic” culture might see the same event spiral into prolonged instability. Historically, pre-American colonial cycles often topped out at Level 2, while the United States has occasionally brushed Level 4 during post-Crisis Highs, but has never sustained it.

In this framework, the goal isn’t to “end the Turnings”, that would be like trying to stop the seasons, but to climb the maturity scale so the saeculum’s natural pulses happen in safer, more productive ranges. The more adaptive and metacognitive a society becomes, the more it can absorb shocks without collapsing, and use moments of renewal to build lasting strength.

Layer One: The Foundational Conditions of Society

Every cycle needs a rhythm: the beat that sets the mood before any political or cultural movement begins. For civilizations, that rhythm starts with foundational conditions: the economic, ecological, technological, and security realities that shape daily life.

When those conditions are stable and supportive — when wages rise, communities feel safe, the environment is predictable, and technology feels empowering — people tend to feel secure enough to plan for the future. Dopamine stabilizes or rises, and the public is more willing to trust, invest, and cooperate.

But when foundational conditions deteriorate, instability cascades. An economic downturn, a major ecological disruption, a wave of destabilizing technological change, or an acute security crisis can all serve as chronic stressors. Cortisol rises, trust erodes, and the population becomes more rigid and defensive, even before formal politics reacts.

Economics as the Primary Driver

Historically, economic health has been the most consistent and measurable of these foundational factors. The post–World War II boom, for example, delivered decades of rising wages, housing stability, and broad opportunity — conditions that kept stress low and optimism high. Conversely, the 1970s stagflation, the 1980s–90s deindustrialization, and the 2008 crash each undercut security and primed society for sharper mood swings.

Other Foundational Forces

- Ecological Stability: A predictable climate, fertile land, and reliable water supplies bolster social confidence. Environmental degradation, extreme weather, or resource scarcity act as persistent stress amplifiers.

- Technological Shifts: When technology is perceived as enabling opportunity, dopamine rises; when it is seen as destabilizing jobs, privacy, or truth itself, cortisol climbs.

- Security Context: Periods of relative peace foster trust and openness; prolonged wars, terrorism, or perceived vulnerability drive vigilance and harden identities.

Why This Layer Matters

The foundational layer doesn’t directly determine the next Turning, but it sets the emotional stage. How people feel about these conditions, and how those feelings spread, is the bridge to the next layer: the society-wide emotional climate.

Layer Two: Dopamine and the Emotional Climate

If the foundational layer is the terrain of civilization, dopamine and cortisol are the weather systems that sweep across it. Prosperity, scarcity, discovery, and disruption are not purely economic phenomena; they are whole-society experiences that shape how people take risks, form coalitions, challenge norms, or defend traditions.

The saeculum isn’t just a cultural pattern; it’s a living feedback loop, the nervous system of civilization in motion. Events and conditions from the previous layer flow into that nervous system as sensory inputs. How they are interpreted and acted upon depends on the balance between two core neurochemical signals: dopamine and cortisol.

When favorable conditions erode — whether through a market crash, climate disaster, disruptive technology, or prolonged insecurity — the society-wide dopamine tone drops and cortisol begins to dominate. Openness gives way to vigilance, trust contracts, and the public grows more susceptible to rigid identities and simplistic narratives.

These chemical shifts don’t always happen overnight. They can build gradually as conditions decay, or spike suddenly in the wake of a Seismic Narrative Shift. Either way, they act as the emotional fuel for Turning transitions.

In First Turnings, the world feels orderly, structured, and optimistic. Cortisol is low, dopamine is steady or rising. Institutions feel trustworthy. Second Turnings (Awakenings) challenge that trust. Disorder and tension rise. Cortisol increases, and with it, rebellion and emotional volatility. Third Turnings (Unravelings) burn out what’s left of the old moral order. As institutions collapse and individualism soars, cortisol often remains elevated, but is met with cynicism, addiction, and distrust. Fourth Turnings bring system-wide stress. Cortisol dominates. Yet in the fire of shared struggle, something shifts: coherence. Clarity. People begin to realign, and dopamine slowly starts to rise — preparing the ground for the next First Turning.

The result is a long biological arc: hope → challenge → chaos → cohesion → hope again. Not in everyone, and not all at once, but enough to shift the emotional chemistry of a society over time.

It’s not only politics or economics that set these chemical rhythms. Ecological systems, long strained by centuries of expansion and extraction, are now feeding into the same loop. Melting ice, dying forests, disrupted weather — these are not just background crises. They are new, chronic stressors that reinforce the very cortisol-driven behaviors making coordinated response harder. In this way, the natural world is no longer outside the circuitry. It’s wired in.

The Neurochemical Logic of the Four Turnings

The Four Turnings aren’t just generational moods; they may reflect distinct neurochemical phases in a civilization’s collective cycle. If dopamine and cortisol shape how people experience trust, risk, rebellion, and cohesion, then each Turning corresponds to a different balance of these two chemicals across society.

This balance doesn’t shift evenly or mechanically. Instead, it builds momentum over time, a kind of emotional resonance curve, where each phase sets the psychological conditions for the next.

Here is how the pattern unfolds:

1st Turning (High): Post-Crisis Rebuilding → Stable Dopamine, Low Cortisol

Society emerges from a Crisis exhausted but unified. The dopamine tone is modest but rising: people feel purposeful, not euphoric. Cortisol, the stress hormone, has dropped after the resolution of conflict. Institutions are strong, trust is high, and people invest in systems and social norms. This is a dopaminergic plateau: confidence without arrogance. The tone is one of recovery, not ecstasy.

2nd Turning (Awakening): Dopamine Buildup → Idealism, Rebellion

As safety stabilizes and material conditions improve, dopamine accumulates, especially among younger generations who didn’t experience the prior Crisis. That buildup drives exploration, idealism, and dissatisfaction with order. A spiritual or moral awakening begins, not because conditions are bad, but because people crave more. Emotional boundaries are tested. Institutions feel restrictive. Cortisol remains low, but social friction rises. This is the peak of dopamine potential energy, seeking release through transformation.

3rd Turning (Unraveling): Dopamine Withdrawal → Fragmentation, Cynicism

Eventually, the dopamine surge hits diminishing returns. Idealism curdles into disillusionment. Institutions weakened by neglect or backlash begin to fray. Cortisol rises as uncertainty returns, but without the cohesion of a unifying threat. Individuals turn inward. Trust breaks down. Self-medication (addiction, entertainment, distraction) replaces collective action. This is a withdrawal state: not just chemically, but culturally. Society loses its shared narrative.

4th Turning (Crisis): Cortisol Surge → Fight-or-Flight Reordering

In the absence of renewal, fragility builds until a rupture occurs. This might be economic collapse, war, ecological disaster, or institutional implosion. Cortisol spikes across the population. The dominant mood is tribal, reactive, and rigid. Yet paradoxically, this shared cortisol environment can produce clarity: a forced narrowing of focus that enables decisive (if sometimes destructive) action. In the fire of the Crisis, new institutions form. Dopamine begins to rise again, not from abundance, but from collective purpose. This chemical shift lays the groundwork for a new High.

This model provides a neurochemical foundation for Strauss and Howe’s Turning sequence. It explains why the cycle has a rhythmic feel, why each phase tends to lead into the next, and why we struggle to interrupt it, because each phase rewires not just culture, but cognition.

It also suggests that any effort to soften the cycle must take this biological sequencing into account. You cannot impose High-trust systems in a cortisol-soaked Crisis. You cannot demand Awakening-style idealism in the grip of dopamine scarcity. But you can build scaffolding that helps societies navigate these transitions more consciously, using chemistry not as destiny, but as context.

Layer Three: Ideology in a Chemical Mirror

If a civilization’s nervous system is tuned by the balance of dopamine and cortisol, ideology is one of its most visible reflexive responses. Mood chemistry shapes the lens through which entire populations interpret the world, and that lens colors the political and cultural beliefs that take root.

When dopamine is high, societies lean “open”: receptive to new ideas, tolerant of uncertainty, curious about difference. Liberalism, in the broadest psychological sense, thrives in such climates, along with empathy, reform movements, and a willingness to take collective risks for long-term rewards.

When dopamine drops and cortisol dominates, the ideological climate tightens. People lean “closed”: craving certainty, clarity, and strong in-group boundaries. Complexity feels dangerous. Rigid ideologies gain traction across the spectrum, whether expressed through authoritarian right-wing nationalism or uncompromising left-wing purism. The axis is not left vs. right, but open vs. closed.

The fingerprints are visible in recent history:

- 1960s (High Dopamine): Economic abundance fuels expansive liberal movements, from civil rights to environmentalism to the space race.

- 1980s–90s (Mixed Dopamine / Rising Cortisol): Economic anxiety grows, political rhetoric shifts toward law-and-order, deregulation, and moral panics.

- Post-2008 (Low Dopamine / High Cortisol): Populist movements surge, trust collapses, and conspiracy theories flourish—not from ignorance, but from a deep psychological need for clarity and control.

The same chemistry-driven shifts appear worldwide. In 1990s South Africa, optimism at the end of apartheid fueled openness; in 2010s Europe, refugee crises and economic strain drove cortisol-fueled nationalist backlashes.

Fear narratives—whether about “globalist agendas,” cultural invasions, or hidden cabals—are not random. They are emotional coping strategies in times when openness feels dangerous. Art and entertainment mirror the same swings: utopian futures in high-dopamine eras, dystopian collapse in cortisol-heavy ones.

Ideology, in this model, is not the driver but the mirror. Leaders and policies emerge from the prevailing chemical climate, and once in place, they reinforce it. This feedback loop means that unresolved tensions from one cycle do not disappear, they accumulate, making each new Turning more brittle and volatile unless deliberately addressed.

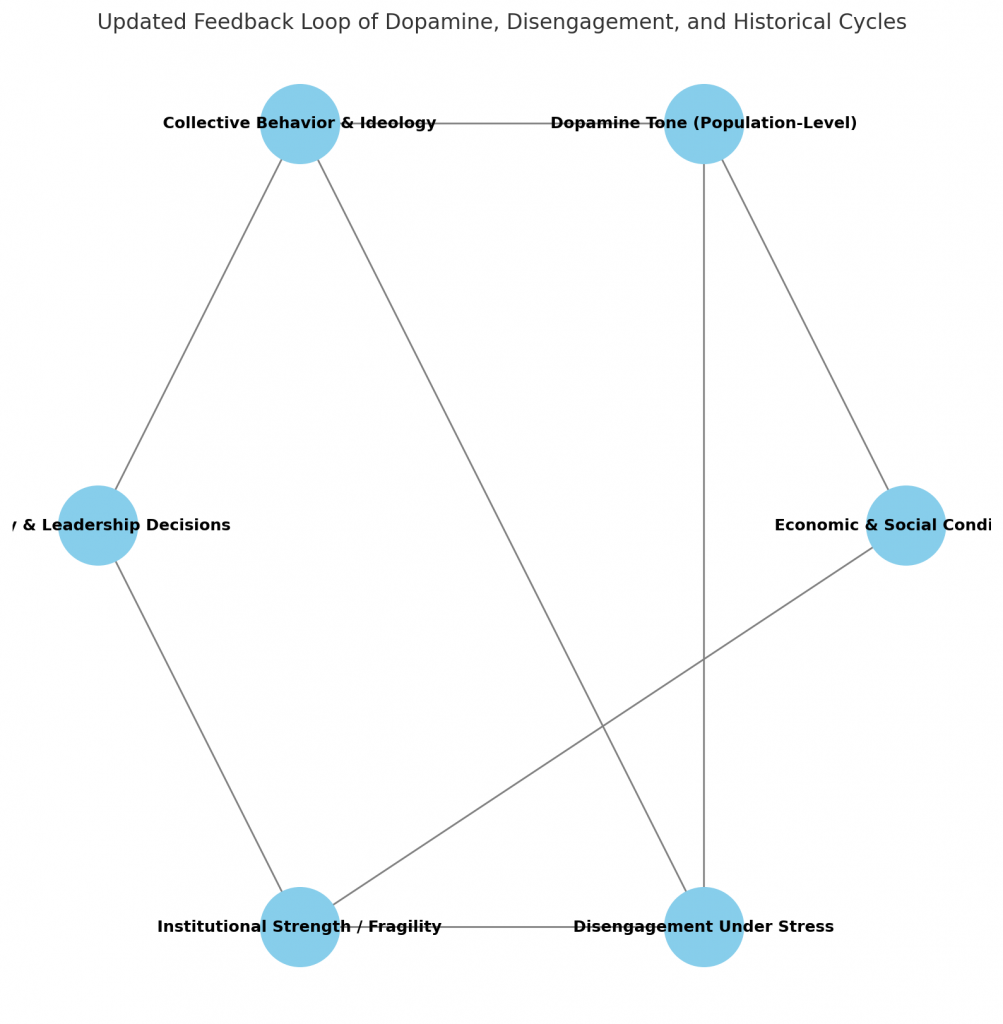

This diagram shows how economic conditions, dopamine tone, ideology, leadership decisions, and institutional strength interact in a self-reinforcing loop.

Layer Four: Policy, Power, and the Mood of the Moment

We like to think of leaders as shapers of history, but more often, they are expressions of it.

Political leaders don’t rise in a vacuum. They reflect the emotional climate of their time, channeling the public’s mood, sometimes skillfully, sometimes manipulatively. And because they hold power, their choices can amplify that mood, for better or worse.

In high-trust, high-dopamine eras, we tend to elect builders, leaders who invest in infrastructure, expand rights, and aim to lift the whole society. Think Roosevelt after the Great Depression, Eisenhower during the postwar boom, or Obama, whose message of hope resonated after the 2008 crash (until the system’s inertia blunted its momentum).

But in low-trust, low-dopamine eras, we often reach for breakers, leaders who promise control, scapegoats, or revenge. They don’t rise because they’re persuasive in some timeless way. They rise because they mirror the desperation of a population that feels betrayed and unseen.

In these moments, cruelty often reads as strength. Societies under stress are drawn to figures who reject empathy, treat negotiation as weakness, and seem willing to “do what it takes” without flinching. Their harshness becomes a performance of clarity, and the absence of compassion is mistaken for courage. This pattern is not new: history has seen it in industrial tycoons, revolutionary zealots, and political demagogues alike, but it is dangerous, because what looks like control often accelerates collapse.

Their policies tend to follow suit:

- Builder Eras: Public goods invested in, institutions reinforced, long-term planning emphasized.

- Breaker Eras: Public goods gutted, institutions attacked, policy reactive and tribal, crisis deepened rather than resolved.

It’s tempting to pin the blame on individual leaders, but the deeper truth is systemic. As Einstein said, “The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch and do nothing.” Even Einstein himself may not have become Einstein without a society primed for a mind like his. If it hadn’t been him in 1905, it might have been someone else by 1915. Societies produce the leaders they are ready for—scientists, reformers, or demagogues—based on the emotional and material conditions already in place.

And when those leaders make decisions under stress, those decisions don’t just change laws; they change trust. That’s when institutions begin to bend, or break.

Layer Five: Institutions—The Breakers or Buffers of the Cycle

Institutions are meant to steady the ship. At their best, they channel society’s energy into productive action: education systems that prepare the next generation, public health that cushions crisis, journalism that informs, courts that hold power accountable.

But institutions don’t run on autopilot. They depend on trust, on leadership, on participation. When economic pressure and ideological rigidity rise, when dopamine falls and fear takes hold, institutions begin to bend. And under enough pressure, they break.

Sometimes that pressure is internal: underfunding, corruption, or partisan rot. Sometimes it’s external: leaders deliberately undermining public trust for political gain. Often, it’s both.

What matters is this: as institutions weaken, they stop moderating the cycle and start amplifying it.

– A justice system that’s seen as rigged encourages vigilante thinking.

– A press that chases clicks over clarity deepens outrage and confusion.

– A government that fails to respond to crisis erodes the belief that anyone is steering the ship.

Weak institutions make low-trust environments feel permanent, and that drags the cycle further down. But strong institutions can absorb shock, preserve empathy, and dampen the volatility that otherwise defines Crisis periods.

They can’t prevent the wave, but they can stop it from crashing as hard.

How Turnings Transition: Seismic Shifts and Shedding

Why this matters:

Knowing how a Turning will change is just as important as knowing when. If we can anticipate whether the next shift will be explosive or gradual, we can prepare for its risks, and its opportunities. Strong institutions (see Section 8) can sometimes absorb even primed shocks without tipping the cycle. Weak ones amplify them.

Not every Turning begins the same way. Some erupt in a moment of clarity, others creep in quietly until we realize the ground has shifted. Understanding these modes is crucial to anticipating the next phase of the saeculum.

Seismic Narrative Shift

A Seismic Narrative Shift occurs when an event, or a tightly linked cluster of events, is interpreted as large enough to reset the public mood almost overnight. This is not purely about material damage; it’s about symbolic and emotional weight. The assassination of John F. Kennedy, the September 11 attacks, or Pearl Harbor each triggered an immediate re-framing of national priorities, identities, and fears.

Neurochemically, this is a cortisol spike hitting a society that’s already “primed” by rising stress. The event doesn’t just happen in history; it re-centers history, creating a “before” and “after” in public consciousness.

Shedding Transition

By contrast, a Shedding Transition happens without a singular rupture point. Instead, old narratives lose cohesion bit by bit. Institutions and norms erode, and people begin to act as though a new era has begun, even if no one can agree when it started.

Neurochemically, this aligns with dopamine withdrawal after a peak. There’s no one “shock” to rally around; instead, the shift is recognized in hindsight. Examples include the slow cultural unravelling of the late Gilded Age or the gradual fading of 1960s idealism into 1980s market absolutism. Another example is the gradual erosion of post–Cold War optimism through the 1990s and early 2000s, as economic inequality and political polarization deepened without a singular crisis event to mark the shift.

Table 2: Turning Stages and Transition Types

| Turning Stage | Neurochemical Climate | Common Transition Mode | Example(s) |

| High | Stable dopamine, low cortisol | Typically Shedding | Post–WWII Consensus (1946–1964) |

| Awakening | Rising dopamine, low-to-moderate cortisol | Shedding or Seismic | 1960s counterculture (Shedding) |

| Unraveling | Falling dopamine, rising cortisol | Shedding or Seismic | Late Gilded Age decline (Shedding) |

| Crisis | Cortisol-dominant, dopamine recovering near end | Seismic | Pearl Harbor (Seismic) |

The Threshold Effect

Both types depend on thresholds. A society can experience mid-sized shocks that fail to trigger a Turning change because the collective mood isn’t ready to reinterpret itself. But when emotional, chemical, and narrative conditions align, even a modest event can tip the scale.

Sometimes, a society will “reject” mid-sized events because they don’t feel like the real turning point yet: a Mid-Event Rejection. When the right-sized, or right-timed, event finally arrives, the shift is swift and widely acknowledged.

The two primary transition modes, and their variants, can be compared side-by-side, showing how neurochemical state, event profile, and public recognition interact to tip a society into its next Turning.

Table 3: Turning Transition Types and Their Characteristics

| Transition Type | Neuro Trigger | Event Profile | Recognition Pattern | Historical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seismic Narrative Shift | Cortisol spike in a primed society | Single large-scale event or tightly linked cluster | Immediate re-framing of national mood; “before/after” narrative forms quickly | Pearl Harbor (1941), JFK assassination (1963), September 11 attacks (2001) |

| Shedding Transition | Dopamine withdrawal after a peak | No single rupture; gradual erosion of norms and narratives | Slow shift recognized mostly in hindsight; no single rally point | Decline of Gilded Age into Progressive Era (~1890s–1900s), Fading of 1960s idealism into 1980s market absolutism |

| Mid-Event Rejection | Elevated cortisol/dopamine imbalance without saturation | Mid-sized event during primed state | Society debates if it’s “the moment”; mood doesn’t fully shift | Early Vietnam escalation (1964–65), 2008 financial crash before later political crises |

| Threshold Event | Emotional and narrative saturation point reached | Event of any size hitting at the right moment | Shift triggered less by scale of event than by readiness to reinterpret reality | Fall of Berlin Wall (1989), COVID-19 pandemic onset (2020) |

What Strauss and Howe described formally, earlier societies intuited in their own way. Long before clocks, surveys, or neuroscience, ancient peoples sensed the same rhythms. What they described as prophecy, we might now describe as circuitry.

📜 Spotlight: From Prophecy to Circuitry

The fire crackles. Elders lean on carved staffs, eyes dim with memory but sharp with knowing.

“The young grow restless. The rituals ring hollow. The gods will demand their due.”

They cannot name the spark — famine, war, or death of a king — only the certainty: something must break; a new age is coming.

Their prophecy was not a script but a recognition. The cycle demanded release.

Today, we clothe the same intuition in science. Cortisol stress accumulates in institutions. Dopamine surges in culture. A feedback loop pushes society toward rupture.

We too cannot name the spark. We can only know the inevitability: a Seismic Narrative Shift will arrive — whether in one shattering detonation or a quiet shedding.

The prophecy still comes true. Only the gods have changed.

This continuity matters. The myths were never empty: they captured, in symbolic form, the same inevitabilities we now measure as stress chemistry and generational dynamics. The language has changed, but the cycle still demands release.

Whether abrupt or gradual, these transitions shape not just the mood of the moment but the feedback loops that carry the cycle forward.

Trigger Sensitivity Across Eras

Pre-Mass Media Era (pre-mid 19th century)

- Awareness Speed: Slow. News traveled via letters, word of mouth, and occasional printed broadsheets.

- Framing Control: Highly local. Interpretation depended on community leaders, clergy, or local newspapers.

- Trigger Likelihood: Low for national mood shifts. Outrage often cooled before word spread broadly.

- Example: Even momentous events like presidential assassinations (e.g., Garfield in 1881) unfolded over weeks, giving factions time to manage or diffuse reactions before they became universally defining.

Mass Media Era (telegraph → radio → early TV)

- Awareness Speed: Hours to days. Telegraph and daily newspapers sped up national awareness; radio brought live coverage; early TV added imagery.

- Framing Control: Increasingly centralized. National papers and broadcasters set the dominant narrative.

- Trigger Likelihood: Higher, as simultaneous awareness fostered more unified emotional reactions.

- Example: The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 created a near-instant national mood rupture because imagery and commentary reached virtually every household within hours.

Modern Instant Media Era (24/7 cable, internet, social media)

- Awareness Speed: Minutes to seconds. Live video, instant social sharing, and push notifications produce real-time collective witnessing.

- Framing Control: Highly fragmented. Multiple competing narratives emerge instantly, but initial frames can go viral before counter-narratives catch up.

- Trigger Likelihood: Extremely high for both single-event and cumulative outrage scenarios.

- Example: The George Floyd killing in 2020 was a textbook Seismic Narrative Shift: a single high-visibility event that instantly crystallized outrage.

- New Dynamic: In the modern era, sensitivity to triggers is not limited to single high-magnitude shocks. Instant and persistent media coverage allows a series of mid-magnitude provocations to be chained together into a cumulative outrage cycle. Each incident re-activates and intensifies the emotional climate, keeping it primed for the next escalation. When the “final straw” incident arrives, its symbolic weight is amplified by the memory of prior offenses, making it feel like a seismic rupture even if no single incident would have been sufficient on its own. This chaining effect was far less common before instant mass communication, when outrage often cooled before subsequent events could reach the same audience.

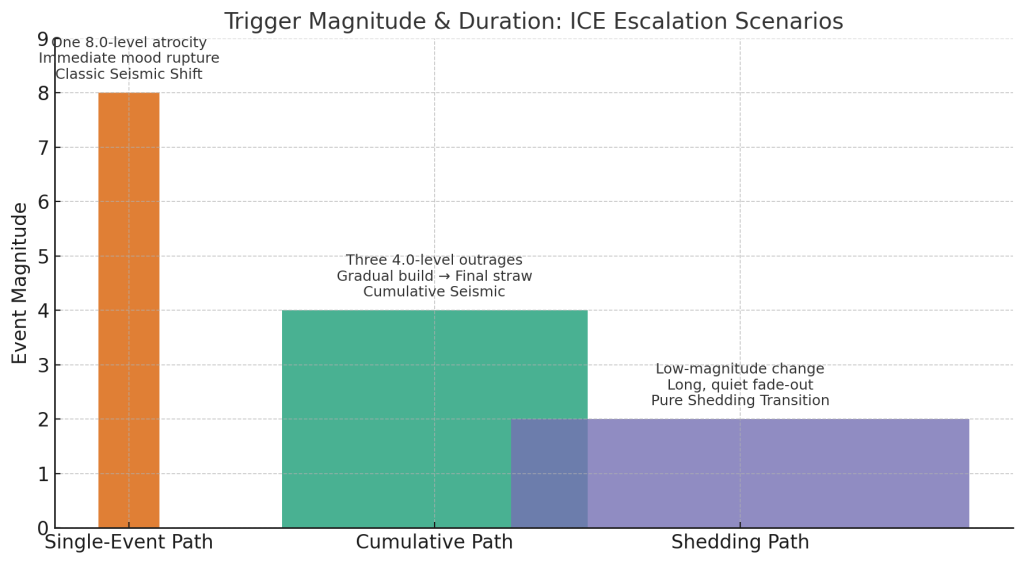

Callout: Cumulative Triggers in Action: The ICE Escalation Scenario

In a primed society, a political leader could deliberately escalate the actions of a controversial enforcement agency like ICE, pushing it toward more visible and morally contested actions.

| Path | Magnitude | Sequence | Trigger Mechanism | Mood Shift Speed | Turning Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Event Path | 8.0 | One incident | An extremely visible atrocity instantly unites public opinion | Immediate | Classic Seismic Narrative Shift |

| Cumulative Path | 4.0 × 3 | Series of incidents | Several mid-level outrages keep outrage hot until a “final straw” incident tips consensus | Gradual → sudden tipping point | Cumulative Seismic (blended with Shedding) |

| Shedding Path | 2.0 | No defining incident | Controversy fades without a symbolic flashpoint | Slow, diffuse | Pure Shedding Transition |

Turning Relevance: Any of these paths could influence the timing or nature of a Turning transition. In the modern instant media era, the first two paths can trigger rapid mood shifts, while the Shedding path represents a low-drama, low-intensity change.

Single-Event Path: One high-magnitude atrocity (8.0) over a short period, causing an immediate mood rupture.

Cumulative Path: Three mid-magnitude outrages (4.0 each) over a longer period, culminating in a “final straw” incident.

Shedding Path: Low-magnitude (2.0), long-duration fade-out with no unifying trigger: a slow, quiet Turning transition.

Closing the Loop: The Feedback Cycle of History

Why this matters:

We’ve explored each layer of the saecular system — from economic shocks to brain chemistry, ideology, leadership, and institutional strength. On their own, each layer is powerful. Together, they form a closed feedback loop, a civilization’s nervous system, that processes its environment and reacts accordingly.

Understanding this loop shows us where interventions can occur, and why similar events can push one society toward renewal while sending another into collapse.

Like a biological nervous system, this loop can operate at higher or lower maturity levels (see Civilization Maturity Model, Section 8).

- At CivMMI Level 4 or 5, a society responds to stress with adaptation and learning.

- At Level 1 or 2, it reacts with reflex and panic.

The same event, striking two societies at different maturity levels, can produce entirely different Turning trajectories.

How the loop works

- Economic & Social Conditions rise or fall.

- These shifts influence dopamine tone at the population level, changing how people feel, think, and relate.

- That mood drives collective ideological behavior: openness vs. rigidity, trust vs. fear.

- These behaviors shape the leaders we elevate and the policies they choose.

- Those decisions either strengthen or weaken institutions, which in turn shape the next round of economic conditions.

And back we go — because the loop never really stops.

This is not just a cycle, it’s a system. A multi-level loop. A kind of circuitry that operates beneath the surface of Strauss and Howe’s Four Turnings.

Just as in software, where stopgap patches accumulate into brittle technical debt, so too do societies inherit unresolved solutions from past Crises. These “legacy fixes” may stabilize one era but quietly erode the next, until accumulated strain overwhelms the system again.

Mapping the Loop onto the Turnings:

- High (Post-Crisis Rebuilding) — Economic optimism → high dopamine → social trust and empathy → institution-building → liberal openness → long-term planning.

- High maturity invests in adaptive capacity.

- Low maturity breeds overreach or neglect.

- Awakening (Ideological Upheaval) — Sustained abundance → dopamine shifts from security to self-expression → generational rebellion → weakened institutions through disillusionment or neglect.

- High maturity channels this into reform.

- Low maturity lets polarization harden into permanent fractures.

- Unraveling (Fragmentation) — Inequality rises → dopamine stratifies (high for elites, low for most) → polarization, cynicism, and addiction → populist leaders and punitive policy → institutional decay.

- High maturity mitigates through redundancy and trust-building.

- Low maturity accelerates decay, priming for a severe Crisis.

- Crisis (Collapse and Realignment) — Widespread stress and fear → dopamine bottoms out → tribalism, rigidity, scapegoating → institutions fail when needed most → new economic order emerges.

- High maturity navigates with cohesion and shared sacrifice.

- Low maturity suffers maximal damage and post-Crisis regression.

This chart shows how each layer of the feedback loop — economic/social conditions, dopamine tone, ideology, leadership, and institutional strength — rises and falls over time, mapping onto Strauss–Howe’s Four Turnings. Each curve lags behind the one before it, creating overlapping waves of influence. The pattern is stable enough to be predictable in form, but volatile in outcome depending on how each layer is managed.

But even if we can buffer the system or recognize the signals in time, there’s a deeper question we have to answer: why does the cycle keep resetting in the first place, even when we see it coming?

To explore that, we need to look not just at systems, but at psychology.

Cortisol and Me

I’ve noticed this in myself. Even when I feel intellectually grounded, I still find my attention fraying. I’ll open a tab to work on something meaningful, and wind up watching a YouTube video instead. This isn’t laziness. It’s my brain, adapting to stress by seeking easy rewards and dodging ambiguity. If this model is correct, then we’re not just thinking differently, we’re being re-wired by the world we live in.

This isn’t fate. It’s momentum. The loop can spin smoothly, or spiral violently, depending on how we manage each layer.

But even when we understand the system, there’s a deeper challenge ahead: how different kinds of people react under stress, and what those reactions mean for the course of the Turning. That’s where we turn next.

The Perpetuation of the Cycle

If the loop is so clear — economics shapes dopamine, dopamine shapes ideology, ideology shapes leadership, leadership shapes institutions, institutions shape economics — why can’t we stop it?

The answer may lie less in our systems than in our own biology.

When a society enters a Crisis Turning, collective action becomes urgent. Institutions are faltering, trust is low, and critical decisions loom. Yet paradoxically, this is the moment when many capable, conscientious people disengage. They stop voting. They stop organizing. They stop believing change is possible.

This withdrawal isn’t just political, it’s neurological. Elevated cortisol narrows focus, erodes agency, and pushes people into retreat. And it hits hardest among the most empathetic, community-oriented individuals: the very people most capable of stabilizing the system.

They’re not apathetic. They’re overloaded.

The Timing Mismatch

This creates a devastating mismatch:

- We need people to override their stress responses precisely when those responses are most intense.

- We need them to lean in just when they most want to pull back.

If they don’t, the system tips, not only because of bad actors, but because good actors stayed home.

This dynamic amplifies earlier meta-patterns:

- Delayed Civic Reengagement — helpers return after the key decisions are made.

- Resilience to Capture — weakened when watchdogs retreat.

- Event Wave Lag — disengaged publics miss the moment when cumulative pressures crest into decisive change.

Stress Responses by Social Orientation

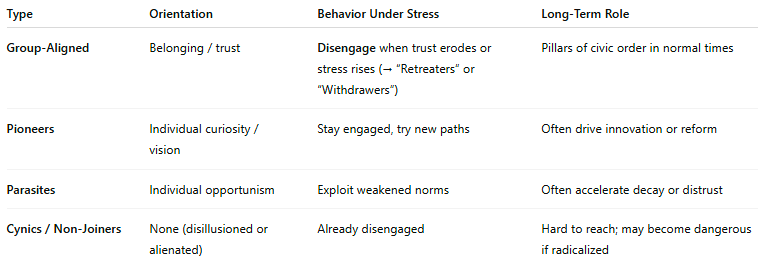

Different people react to crisis stress in different ways, and their choices shape long-term civic outcomes. Understanding these patterns is key to anticipating who will step up, who will step back, and who will exploit the moment (see Figure 4 below)

Figure 3: Social Orientation Spectum

Why the cycle resets

Disengagement isn’t the sole cause — structural inequality, elite capture, and institutional decay all matter — but when empathetic participants retreat, those forces meet less resistance and grow stronger. The vacuum left by Disengagers doesn’t stay empty; it fills with opportunists, demagogues, and actors less constrained by empathy.

Even when Disengagers return — after cortisol ebbs, after chaos cools — the world has shifted without them. Institutions may have been restructured, norms rewritten, coalitions formed in their absence. Reentry can trigger alienation or backlash:

“We didn’t vote for this.”

Even if they literally didn’t vote.

Their long silence becomes a political force — not through direct action, but through timing — and that force can help launch the next Turning.

Breaking the pattern

If we want to soften the Turnings, we must address this mismatch directly: building systems, stories, and scaffolding that keep people engaged even when every instinct says to retreat. Without that, the loop will keep spinning, and history’s circuitry will keep resetting itself, no matter how well we think we understand it.

Can We Soften the Cycle?

Why this matters:

We can’t escape the wave, but we can change how it hits. The generational Turnings described by Strauss and Howe aren’t laws of physics, but they do reflect something deeply human. Our societies, like our bodies, move through cycles of expansion and contraction, confidence and doubt.

If the model in this article is right: that our economic systems influence our brain chemistry, which in turn shapes our politics and institutions, then the cycle is more than historical. It’s biological. It’s emotional. And that means it’s knowable.

We don’t have to stop the cycle to make progress. What we need is to find points of leverage, small interventions that shift the tone of a generation, and help civilization climb the maturity scale (CivMMI) so the saeculum’s natural pulses occur in safer, more productive ranges.

Potential leverage points

- Economic buffering: Reduce chronic insecurity through policies like universal healthcare, housing stability, or basic income to prevent mass dopamine collapse.

- Empathy as infrastructure: Treat social trust as a public good. Fund schools that teach perspective-taking. Favor restorative justice over retribution.

- Strengthen institutions early: Rebuild transparency, accountability, and civic trust before the Crisis hits, not after things break.

- Recognize the midpoints: Each Turning has a moment where the mood shifts. Knowing the difference between a Seismic Narrative Shift and a Shedding Transition can help steer not the wave itself, but how hard it crashes.

- Prevent reentry shock: When Disengagers return after a Crisis peak, they often find a world that feels alien. Keep them partially engaged through low-stakes civic scaffolds, stress-aware communication, and systems that welcome reentry with clarity instead of confusion.

If history moves in pulses of fear and hope, the task isn’t to flatten the line; it’s to preserve empathy through the troughs and extend wisdom through the peaks. Recognizing the circuitry is only the first step.

The next challenge is architectural: redesign institutions not to escape the cycle entirely, but to soften its extremes and lengthen its arcs. The reset often begins not with triumph, but with relief. As cortisol subsides and stability returns, dopamine rises. Trust rebuilds slowly, creating the emotional space for reconstruction.

But unless we design this reset with intention, the next cycle will carry the same fault lines forward. The future will always bring another Turning. The real question is: what kind of people will be standing when it comes?

Table 4: CivMMI Maturity Levels and Cycle-Softening Interventions

| CivMMI Level | Typical Crisis Response | Cycle Risk Profile | High-Impact Interventions | Expected Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 – Chaotic | Reflexive, fragmented; scapegoating; no coordinated planning | Severe damage; institutions collapse; long recovery lag | Basic survival infrastructure; emergency trust-building measures; anti-demagogue safeguards | Prevents complete system breakdown; preserves minimum continuity |

| Level 2 – Ritualized | Reliance on tradition or rigid precedent; limited adaptability | Crisis repeats with similar fault lines | Introduce adaptive training for leaders; limited economic buffering; targeted anti-corruption reforms | Opens space for partial reform; slows damage spread |

| Level 3 – Self-Aware | Recognizes cycle but struggles with broad buy-in | Moderate to high damage; some reforms stall | Widespread civic education; empathy as infrastructure; proactive midpoint recognition | Shortens recovery time; improves public cooperation |

| Level 4 – Adaptive | Uses data and foresight to anticipate stress points | Lower damage; institutions retain trust | Early institution strengthening; economic buffering; stress-aware leadership pipelines | Maintains trust through Crisis; preserves reform momentum |

| Level 5 – Metacognitive | Actively manages mood cycles; long-term resilience planning | Minimal damage; crisis energy channeled into renewal | Continuous civic scaffolds; intentional reentry programs; structural anti-fracture design | Extends arcs between severe cycles; smooths wave amplitude |

These maturity levels were first introduced in Section 8: The Civilization Maturity Model (CivMMI) as a way to measure how societies respond to stress. Placing them here, alongside targeted interventions, closes the loop: the same model that diagnoses a society’s readiness also points directly to where effort will yield the greatest benefit. If we can raise maturity even one level before the next Crisis crests, the wave will still come, but its impact will be smaller, recovery will be faster, and the saeculum’s next arc will begin on stronger ground.

Appendix: Generational Snapshots in Neurochemical Context

These short portraits show how the neurochemical climate of a generation’s formative years can leave lasting fingerprints on its worldview. Each example blends history, emotional climate, and dopamine–cortisol dynamics.

The Lost Generation (born c. 1883–1900)

Formative Climate: Late Gilded Age into Progressive Era — high dopamine optimism from industrial growth, new technologies, and expanding cities.

Neurochemical Tone: Rising dopamine without strong guardrails, fueling experimentation, risk-taking, and restless ambition. Cortisol low in youth, but spikes sharply in adulthood with the shocks of World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic.

Result: A generation primed for exploration and reinvention — the jazz age expatriates, bootleggers, and early aviators. But their peak collided with global Crisis. Many entered midlife disillusioned, carrying both the thrill of having lived through an age of expansion and the trauma of a world order collapsing around them.

The Silent Generation (born c. 1925–1942)

Formative Climate: Great Depression through World War II — sustained high cortisol environment marked by scarcity, rationing, and strict social order.

Neurochemical Tone: Elevated cortisol in formative years encouraged vigilance, conformity, and rule-following. Dopamine restrained by uncertainty, only rising with postwar stability in young adulthood.

Result: An adaptive, cautious, institution-trusting generation. They valued order and cooperation, but often avoided open conflict. Their collective wiring made them effective stewards of systems built by others, but less inclined toward radical transformation.

The Millennial Generation (born c. 1982–2004)

Formative Climate: Childhood in the relative calm of the late Unraveling, adolescence in the cortisol spikes of 9/11, the War on Terror, and the 2008 financial crash.

Neurochemical Tone: Early-life dopamine from technological novelty and a sense of global connection, undercut in adolescence by chronic cortisol from economic precarity and security fears.

Result: A generation shaped by both openness and caution — optimistic about innovation and inclusion, yet deeply skeptical of institutions’ ability to deliver stability. Often collaborative and purpose-driven, but carrying an undercurrent of economic anxiety that colors their risk tolerance.

Why These Matter

These sketches are not destinies; they’re predispositions. They show how formative emotional climates, shaped by dopamine and cortisol levels, can tilt a whole cohort’s default settings toward openness or caution, trust or skepticism. In turn, these generational tilts feed back into the larger saecular cycle, influencing the mood of each Turning.

References & Influences

This framework draws on research, historical analysis, and conceptual models from multiple disciplines. The following works have been especially influential in shaping its development:

Core Theoretical Foundations

- ★ Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow.

- ★ Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1997). The Fourth Turning. New York: Broadway Books.

- ☆ Turchin, P., & Nefedov, S. (2009). Secular Cycles. Princeton University Press.

- ☆ Turchin, P. (2016). Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History. Beresta Books.

- ★ Turchin, P. (2023). End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration. Penguin Press.

Neuroscience & Psychology

- ★ Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers (3rd ed.). Holt Paperbacks.

- ☆ Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Press.

- ☆ Zmigrod, L. (2020). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Ideological Extremism. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 21(9), 504–516.

- ☆ Friston, K. (2010). The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

- ☆ Wallace, A. F. C. (1956). Revitalization Movements. American Anthropologist, 58(2), 264–281.

Systems Thinking & Complexity

- ★ Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press.

- ★ Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- ☆ Rockström, J., et al. (2009). A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472–475.

Economic & Historical Analysis

- ☆ Fischer, D. H. (1996). The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History. Oxford University Press.

- ☆ Dehio, L. (1962). The Precarious Balance: Four Centuries of the European Power Struggle. Vintage Books.

- ☆ Modelski, G. (1987). Long Cycles in World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Cultural & Moral Psychology

- ★ Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books.

- ★ Lakoff, G. (1996). Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. University of Chicago Press.

Additional Influences

- ☆ Beck, D., & Cowan, C. (1996). Spiral Dynamics. Blackwell Publishing.

Related Works by the Author

- Kephart, G. (2024). The Hidden Circuitry of the Four Turnings.

- Kephart, G. (2024). A Tale of Future History.

If you’re aiming for a self-study sequence while you’re still reading through these, the ★ entries would give you a solid HC foundation in about 6–8 books/articles, and then you could layer in the ☆ works for depth and academic rigor.

Readers interested in exploring these sources further are encouraged to consult the original publications. Where applicable, references have been selected for their clarity, relevance, and accessibility to non-specialist audiences.

Author’s Note:

Thanks for reading. This piece started as a personal attempt to map how history, brain chemistry, and politics might all fit together. It’s part pattern recognition, part reflection, and part wondering if we can do better next time.

I’d love to hear what this sparked for you—whether here in the comments or in conversation somewhere down the line.

This is a great article! Very well written! You should definitely consider expanding on the topic for a book.

Thank you! I’m glad you liked it! 🙂

I actually have a series of articles planned out. The next one is devoted to providing more proof that this theory is correct. After that will be a series of institutional patterns.